EU Lithium Mining Deal with Serbia Sparks Protests

EU projects12-fold increase in lithium demand for batteries from 2020 to 2030

EU’s Lithium Deal With Serbia Sparks Protest

Protests erupted in Serbia after the Balkan nation signed a strategic partnership agreement with the European Union (EU) to develop a lithium mine that will help the bloc reduce its dependency on non-European suppliers and pursue its clean technology ambitions.

Lithium mining is a controversial topic in Serbia, and concerns about environmental impacts and mining rights have sparked fierce debate in the country. Protests erupted across Valjevo, then spread to the rest of the country in solidarity with this lithium-rich Western region.

“We’ve gathered to seek answers,” Serbian movie director Zoran Đorđević, who is also a Brazilian resident, said for N1 television. “It is obvious that corruption is in question, as with everything else in this country. I am interested in people’s opinions. Do they want lithium? I don’t want a mine here, as I know what it means to have a mine near the town.”

Serbian environmental activists and local communities had already raised their concerns about the potential ecological damage of the lithium mine. In 2022, mass protests led the Serbian government to ban mining giant Rio Tinto (LON: RIO) from starting extraction, citing environmental concerns. Although the ban was later deemed unconstitutional, the incident showed the deep mistrust and opposition to Rio Tinto's operations.

Rio Tinto actively engaged the public through press releases, arguing against numerous statements from Serbian media, deeming them factually incorrect. The company argued that independent scientists had made environmental impact assessment studies by the legally defined process without influence on their selection.

Green Transition Cornerstone

For the EU, the agreement marks a significant step in its quest for critical raw minerals. It establishes a roadmap for lithium production, battery supply chains, and electric vehicles (EVs). It could also help the 27-member bloc reduce imports of critical raw materials from non-European nations, including 100% of the heavy rare earth elements it buys from China.

The EU's Joint Research Centre projects a twelve-fold increase in lithium demand for batteries from 2020 to 2030, driven primarily by the transition to EVs and renewable energy technologies. Lithium is crucial in batteries for EVs, solar panels, and wind turbines, which are vital for a sustainable, fossil fuel-free future.

The EU is far from self-sufficient in lithium production, with only significant production in Portugal. Except for Serbia, there are known deposits near the German-Czech border, Extremadura, Spain, Carinthia in Austria, and Alsace in France.

Currently, the EU relies on imports from leading global producers like Chile, and this dependency is problematic, especially as global competition for lithium intensifies.

Serbia has also become geopolitically important for the EU as it tries to stem the influence of China in Belgrade, which applied for EU membership in 2009, with little progress made in joining the bloc since then. Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Belgrade in May when he met with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic. They signed an agreement to build a “shared future,” making the Balkan country the first in Europe to agree on such a document with Beijing.

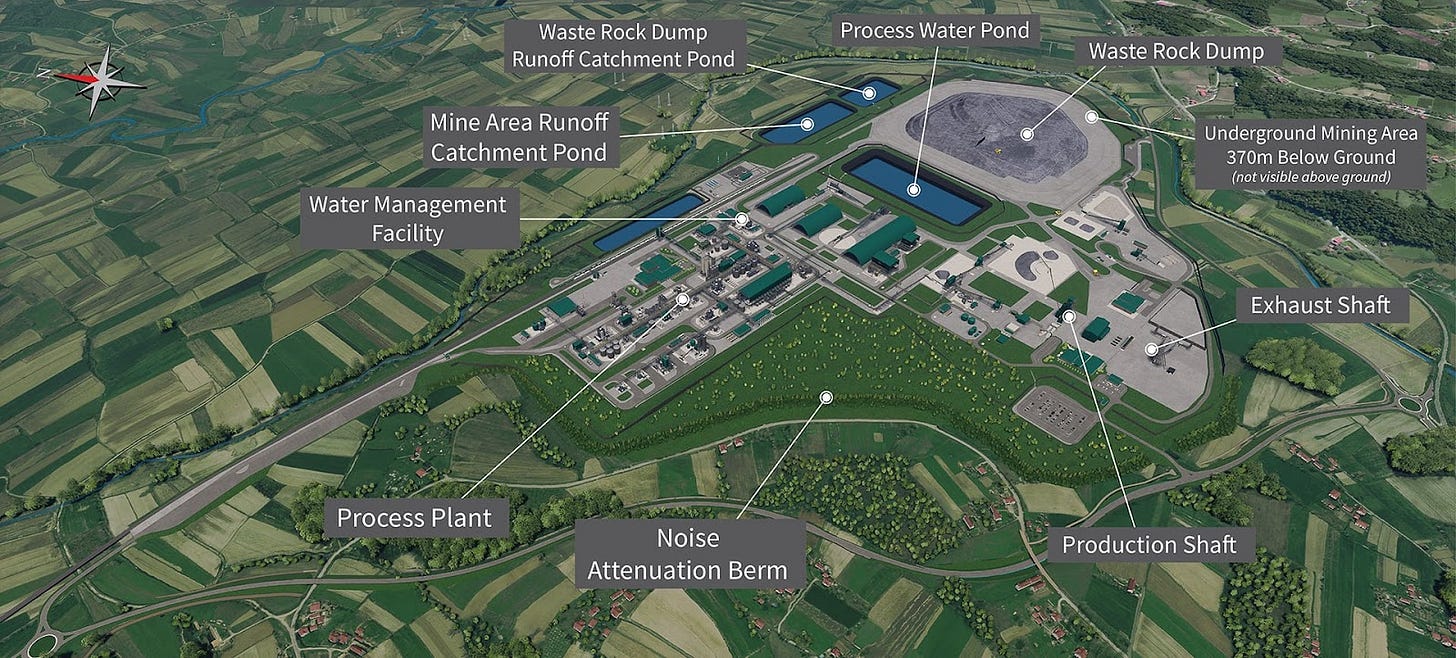

Jadar Project

The focal point of the EU-Serbia lithium deal is the Jadar project, located in the Jadar Valley in western Serbia. This project involves mining jadarite, a lithium-boron mineral unique to the area.

Unlike lithium extracted from brine, an oil byproduct, jadarite requires old, less environmentally-friendly extraction techniques such as evaporation. This type of mineral is unique to Serbia since typical lithium sources include either lithium-enriched brines or lithium pegmatites (a type of granitic rock).

The Jadar project promises significant economic benefits, including 1,300 new jobs. It would be one of the largest foreign direct investments in Serbia's history, worth at least €2.55 billion. Estimated production includes 58,000 tons of lithium annually, enough for 1 million EVs.

While the Jadar mine would produce lithium, it could also cause serious damage to the local environment—the invisible cost that a producer can quietly offload onto society.

Chinese economist Niu Wenyuan developed a “green GDP” method to measure economic output while deducing negative externalities. Wenyuan argued that not only do conventional growth measures fail to register such negatives, but they eventually record them as positive. For example, a clean-up of a polluted river would also create GDP-inflating activity.

Rio Tinto Controversy

The involvement of Rio Tinto in the project adds another layer of controversy. The company has faced criticism and protests over its global environmental record.

Communities near its QMM mine in Madagascar have recorded uranium and lead levels over 40 times in excess of WHO’s safe drinking water standards. The residents of Papua New Guinea accused the company of inadequately dealing with the waste from its former Panguna mine.

“We are always worrying that the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe is not safe,” Theonila Roka Matbob, a member of parliament in the Asian country, said. “Work to address the impacts identified by the environmental and human rights assessment cannot come soon enough.”

In July 2021, Rio Tinto and Bougainville community members reached an agreement to identify and assess legacy impacts of the former Panguna copper mine in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. Rio Tinto said at the time that it took “this seriously“ and was “committed to identifying and assessing any involvement we may have had in adverse impacts” on the community.

‘Neocolonialism Stance’

Serbian criticism of Rio Tinto’s operations goes beyond the environmental impact.

Radar’s journalist Luka Petrusic pointed at reports of Rio Tinto subsidiary Rio Sava, established in 2001 to conduct geological exploration activities in the Balkan country, spending €155 million on consulting services, such as feasibility studies.

Petrusic called for an evaluation of whether those services got billed at inflated, unrealistic prices, while economist Bozo Draskovic took a different angle, pointing at this cost as a way for the government to use the threat of an international arbitrage to justify their actions to the people.

“It’s a game that works between multinational companies and the government,” Draskovic said. “Even the former prime minister mentioned the danger that Serbia could suffer the costs because we prevent the company from profiting here. People who lead this country took that neocolonialism stance and inflating the costs allows Rio Tinto to seek damages in the international court.”